Recently I made a documentary about the movie Foodfight! which I titled ROTTEN: Behind the Foodfight. My memory is a little hazy, it doesn't help this took a few years to happen, but I'm gonna try explaining as best I can how this all came together.

From what I remember, my interest in the film Foodfight! started, unfortunately, with JonTron's review of the film in 2014. I was a big JonTron fan at the time, I've seen all of his videos to a certain point, but for some reason Foodfight was probably the most memorable. This must have been around 2015, I was probably 12, and I don't think Foodfight ever really left my mind since then. Not to say I spent every day thinking about it, but it would come to mind every now and then.

For those who are new to this, Foodfight! is a 2012 animated film produced by Threshold Studios, the same company behind Mortal Kombat (the movie) and Beowulf. It took approximately 15 years to produce and is considered one of, if not the worst animated film. Because of this it's been quite the topic on YouTube ever since the genre of "commentary YouTuber" came to fruition. If you review movies or animation on YouTube, you've probably reviewed Foodfight, and if not, someone's probably asked you to.

Interestingly, as I would actually begin researching the production of this film- which was around 2021 when I was seriously looking into it- I would discover that we didn't really know all that much, and what we did know seemed... off. At the time, the gist of what we knew about Foodfight's creation was the director wasn't familiar with how to direct an animated film, sponsors constantly pulled out, and that the entire film was stolen in 2002 and it had to be remade from scratch.

That last part is what really intrigued me, as well as everyone else. Foodfight is interesting already just because of how bad it is, but the fact there's an entire heist attached to it and might actually be a reason why it's so bad, then that makes it far more intriguing.

In 2022, I started a YouTube channel Ok so..., a little channel dedicated to videos about somewhat niche subjects. Since the beginning I wanted to create a video about Foodfight, but I knew it would be pretty massive, so I had to start from scratch and let it grow.

Interestingly, before I came in, it seemed nobody had really interviewed the people that created this film. There were a few quotes in a few old articles, namely one in particular in the New York Times, but from what I could tell nobody had really talked to the crew after the movie had garnered its infamous status. To tell a story properly, you have to talk to the people who experienced it.

I started at the basics, where do you find the credits for people that worked on a movie in a convenient list? IMDB! I went to Foodfight's page, hit print, and a minute later I had six sheets of names to go through one by one. I started with the art department, knowing that it would be virtually impossible to contact any of the cast, and went from there.

Initially I had no luck getting in touch with the big three producers; Larry Kasanoff, George Johnsen and Joshua Wexler. I considered these lost causes for the longest time, however that would change later.

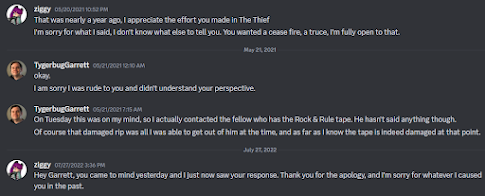

I started by contacting people on LinkedIn, the hub of all business. This proved to be fairly effective, but, many times those who I had reached had no interest speaking over the phone. Aside from LinkedIn I also tried ArtStation, email, Instagram, Facebook, anything. Sometimes, they had no interest in talking at all. It seemed Foodfight had really done a number on some people, and some of the responses I'd get would be like this:

|

A variety of responses I received when asking about Foodfight.

|

Interestingly, out of the people that said no, only two left it as simple as "not interested." The rest described their reasoning in such a way that it would destroy their lives. Eventually, though, I did begin to make some connections. Early during my research I was given a tip that the son of Chef Boyardee's lawyer had expressed interest in animation and Threshold sent him a packet in the mail to see if he'd be interested in a job with Threshold. This packet contained a script to the film, copies of news articles about the studio, character designs, environment designs, and packaging designs. For the longest time, this was our first and only source of concept art from Foodfight!

Later I got in contact with Loressa Clisby, an animator and script supervisor that worked at Threshold during the mid 2000s when they were transitioning to motion capture. Loressa was very open about her time there and was more than helpful. She provided a statement she had previously provided Empire Magazine around 2011 about her time at the studio. Apparently, Empire was going to do an article on Foodfight's production, but the allegations against the studio and Kasanoff were so big they didn't feel comfortable publishing it.

We spoke for a few months over email and after a while Loressa was kind enough to pack me a very large zip file of what she had left over from her time at Threshold. This contained models from the early version of the film (and Dex's office from the later version), behind the scenes photos, another script, character designs, and bloopers. It was a massive discovery and I cannot thank her enough for taking the time to round it up for me. Loressa's statement also gave quite a bit of important information such as a witness account that the assets that were reportedly stolen in 2002 were still present in their servers, that Larry did bring his dogs to the studio often, and that production as a whole was overly chaotic. There were already theories and anonymous accounts that the movie was never stolen, but now we had something a little more concrete.

|

Loressa supervises motion capture performances with the script at the House of Moves mocap studio in 2006.

|

As time wore on I had made the decision with my mother that it may be best to shelve the documentary. So many warnings and red flags about Kasanoff's flesh-eating lawyers and stories about people losing their jobs after talking to the New York Times made us both nervous about my future. So, for a few months, Rotten was canceled.

It wasn't until I spoke with a colleague that I would make the decision to bring it back from the dead. That colleague is Kevin Schreck, a documentary director most well known for his documentary The Persistence of Vision. After a very long conversation about Rotten and documentary making we had decided that reducing this only to a YouTube video (because at the time I was considering making it a bit bigger) will significantly reduce the chance of getting in trouble. It's just a YouTube video, what's the worst that could happen?

And he was right.

I pulled up my old notes and back to work I went. I discovered that there were basically two entirely separate teams that worked on Foodfight. Between 2000-2005, Foodfight was being animated and rendered in the software Lightwave. After that, it was switched to Maya. Because of this change, essentially everyone that was trained in Lightwave was let go when the transition happened and an entire new team was hired to work in Maya instead. So since the Lightwave version (which was only about 10 minutes of finished animation if you're being generous) was scrapped, the only credited animators you'll see for the movie are for the final Maya version. This raised a problem; how was I going to know who worked on it before the change?

Thankfully, someone in the art department, who had been on the film for nearly its entirely duration, came to my rescue. Anonymously, he agreed to give me a list of the people he remembered working with there. This was a massive help and by adding that list to the people already officially credited on the film I was beginning to round up a pretty good amount of leads. Second editor Craig Paulsen was the first person that agreed to be interviewed over the phone. Craig's experience was fairly unique and one of the more positive experiences I heard from. He had mentioned he still had an early cut of the film on DVD and was open to sharing it, however later on he got cold feet and changed his mind. Given that he still works in the industry, this was a decision I could respect. Much of Craig's recollection of what went wrong at Threshold would be chalked up to "well that's just how Hollywood is." Interestingly, Craig wasn't the only person to say this, which is kinda leading me to believe it's true.

The more people I contacted, the more people I found that were open to talking. I was very happy to speak with G.J. Echternkamp, Mr. Clipboard's mo-cap actor. Echternkamp's surreal walking performance was actually derived from a dance he did on YouTube. Until then, I had thought that Mr. Clipboard's iconic stumbling march was animated by hand. I also interviewed R.C. Montesquieu (who requested to be off record,) Greg Emerson (who unfortunately I couldn't find any quotes that would fit), and Neil Fordice. Neil was a modeler on the film during the Lightwave era, most notably doing environment models to which I was shocked to find still displayed on his website. (%90 of the time, people have scrubbed Foodfight from their demo reels, portfolios and resumes.) Neil was a lot of fun to talk to and gave a lot of new insight on what it was like on the film's first crew. His experience seemed to be mostly positive, even mentioning how sometimes they would have games out on a basketball court outside the studio building.

Neil was nice enough to mail me a box of about 75 tabloid print outs of Foodfight's environment designs and storyboards. Originally, he had used these in his apartment and had them tacked up on his walls for reference during modeling when working from home. (Working from home was surprisingly fairly common during the Lightwave era.) The photo at the beginning of this post are those print outs. I had even gotten in contact with the Foodfight sound book illustrator, who was kind enough to send some thumbnails of an unpublished Foodfiight! coloring book. Later on the Foodfight subreddit a user by the name of Tiffany Amber had discovered a copy of the Foodfight! novelization and posted it on the Internet Archive. Immediately I sent her a DM and got her on board. She's been an awesome member of the team and sometimes makes me feel like I'm not a big a Foodfight fan as she is. I also discovered Ubern on Reddit, who initially tried to pull a hoax by modeling Dex and saying he had found the real assets (ironic given that later on we would find the real thing.) His modeling skills and interest in Foodfight felt useful and I recruited him as well. We three still talk constantly to this day.

|

Pages by Ron Zalme for an unpublished coloring book.

|

Surprisingly, there was someone who was actually excited to be interviewed about her experience at Threshold, that being texture artist and animator Mona Weiss. Mona gave a very long and fun recollection of her chaotic time there, an interview I will likely be releasing in full in the future as long as she's okay with it. Mona was the only one of two women who were open to talking to me. Threshold at the time was built greatly on men's entertainment and was a very masculine environment, so getting a woman's point of view always seemed to really point out everything wrong that happened there. Very slowly, my understanding of what it was like working at Threshold

grew from nothing to understanding nearly anything they would mention.

Eventually, interviews and recollections started sounding the same. I

felt as if there was nothing new to learn. One person I was dying to speak to was character designer Jim George. Who, after a lot of research, I discovered became a stillness coach and had entirely retired from animation. I had eventually gotten in touch with his business partner to try to get through to him. His business partner had never heard of his animation history. Apparently, according to George Johnsen, Jim never talked about his past and much of his life is a mystery (even saying that Jim was once a member of Oingo Boingo?) Unfortunately, I never heard back.

Around the time I had finished all my scheduled interviews I began to put Rotten together. I had my partner, Ko Laluna, play the part of Loressa by reading quotes from her statement, as well as getting my father and a family friend to read a few quotes from anonymous interviews I had conducted with crew members. Ko's performance, of course, was fantastic and their "oh, Lady X" bit in the documentary seems to have made a few people chuckle. There's a part of Rotten where I had a bunch of people voice different forum posts about the movie that were made in the 2000s. For this, I had to ask basically everyone I thought might be interested. I thought it would be a fun easteregg as well if I got some of the lost media YouTubers in on it. Gratefully, RebelTaxi, LSuperSonicQ, and blameitonjorge accepted. My colleagues that helped with Rotten also provided voices (being Tiffany, Ubern, and Maxx.)

During the editing of the documentary I actually got in touch with George Johnsen, one of the producers of the film who hadn't talked about it since he left Threshold in 2007. It was a very enlightening conversation and to this day I enjoy catching up with him on the occasion.

Much of the actual compositing of Rotten was fairly normal and not much to report. I was going to fully recreate Threshold Studios as it was in the early 2000s and make some crazy renders with it for the doc but I got too lazy and that never happened. As for the music, I put out a casting call for any musicians that would want to go pro-bono for a documentary I was making for fun. On Discord I was messaged by John Taylor, who worked very quickly and was very receptive to my vague musical requests to create part of the soundtrack to Rotten. Mid-production, John got a new job and could no longer compose for me. Which was fine, but I had to find music to fill in that empty space. So, by combing music from the film during interviews (which at the time I had to rip myself using a 5.1 mix of the audio) and some music from a friend of mine, JoeyVFX, Rotten's weird little pilotredsun-esque soundtrack was in.

I tried to be as neutral as possible in Rotten. I still didn't really know whether or not the alleged 2002 theft really did happen, I didn't want to badmouth Kasanoff directly in case I got sued, and it's just good journalistic practice. When it was released I was very happy with the reception it received and was so glad I was finally able to put some ancient myths to rest. They never finished the old version of the film, the movie was never stolen, and it didn't cost $65 million dollars (an anonymous source would clarify for me that it was actually under $32 million.)

After Rotten was released, of course, I would discover new things I really wish I knew before I had released it. I would learn more details about Kasanoff's house fire (a story I still am not allowed to tell,) Threshold's studio flood (ever wonder why the floor is wet in Rotten's poster?), and, most notably, what ever happened to that Foodfight video game.

I learned a variety of other anecdotes later that I'd like to mention. Supposedly, one of Foodfight's investors was a gang of "Yakuza looking dudes." Which visited the studio to check out how it was going, to which Larry would hide from and just tell the crew to play Hershey's Really Big! 3D Show and just tell the gang that it's Foodfight. Also, apparently Mr. Clipboard was a later addition to Foodfight's story. Originally, Lady X was a robot (the size of an Ike) being piloted by Professor Plotnik (yes, he's literally that small), the mascot for prunes. Plotnik's plan was to take over Marketropolis with prune-creatures. Apparently this version of the story only exists as the 1997 treatment that so far nobody I've managed to contact knows the whereabouts of.

I would later try calling Joshua Wexler one more time and, as if my miracle, he responded as he was driving his car. Joshua had told me that a theft definitely occurred at Threshold Studios, however he wasn't sure what was stolen. We know the files to the movie weren't it because we have them in our possession. It's possible it was something physical, but as of right now it's still a mystery. According to another crew member, the FBI really did come to the studio and question crew members. We know for sure, however, that the movie itself was never stolen and the entire theft was likely used as an excuse to restart production due to Larry's inexperience with authentic animation. Of course, that part is covered in Rotten.

Eventually we sorted everything we had recieved during the research and development of Rotten into the Foodfight Archive, which has every piece of concept art, assets, documents, and anything else we got from the making of the documentary. I'm really happy to present all of these things to the public for free for their own research, and hope there's a possibility that more crew members will come forward and contribute what they have to this weirdo preservation effort.

Anyway, that's about all I got. If you have any Foodfight questions feel free to email me at ziggycashmere@gmail.com.

|

The 3D recreation of Threshold was later repurposed into the poster for Rotten, which my colleague Ubern was kind enough to contribute to with rigs and character models.

|